The Rise of Mining Attacks

Note: this is the second installment in a 3-part post. Read part 1 here.

Monero—a cryptocurrency like Bitcoin, but without a public ledger—is basically at the center of all of today’s cryptomining threats. In fact it’s been estimated that over 85% of all illicit mining is on the Monero blockchain. Most of these attacks utilize an open source miner called XMRig and will use exploits to gain credentials and spread laterally throughout the network. They do this using the Shadow Broker exploits you probably already heard of during the famous WannaCry ransomware outbreak in 2017.

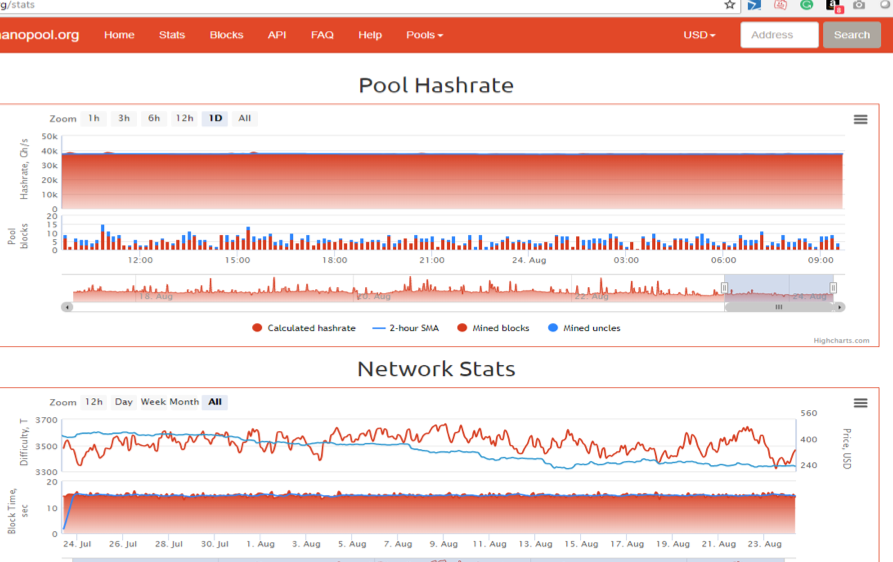

The core idea is very simple: infect a victim with a legitimate, benign miner executable. Run the miner without the victim’s knowledge for as long as possible and monitor its hash rate using a portal that legitimate miners use, because they have no idea that you’re doing this illegally. It’s pretty sneaky.

This isn’t money out of thin air. Users are still on the hook for CPU usage, which they pay for in the form of an electric bill. While criminals usually only mine a small amount of cryptocurrency per machine per day, it adds up fast when you’ve infected almost a million machines.

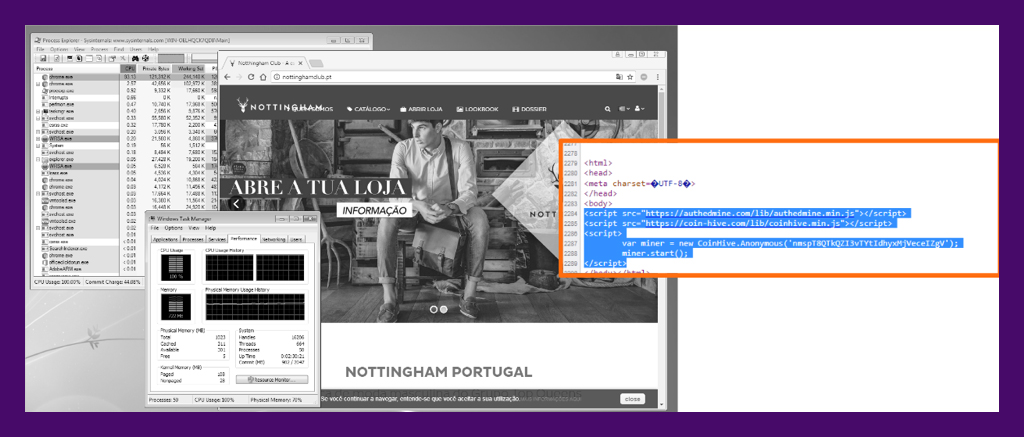

Now, let’s consider this: what if cybercriminals could generate money from victims without ever delivering malware to their systems at all? This threat, called “cryptojacking,” has gained momentum since Coinhive first debuted its mining JavaScript code in September 2017. The original purpose of cryptomining scripts, as described by Coinhive, was to monetize site content by enabling visitors’ CPUs to mine Monero for the site’s owners. While it might not be a noticeable amount for one individual, the cryptocurrency mined certainly adds up for site owners with a lot of visitors. While Coinhive’s website called this an ad-free way to generate income, threat actors are clearly abusing the tactic at victims’ expense.

In the image above, we can see how visiting a Portuguese clothing website caused the CPU to spike to 100%, and the browser process used as much CPU power as it could. If you’re on a newer computer and not doing much beyond browsing the web, you might not notice a spike like this. But, on a slower computer, just navigating the site would be noticeably sluggish. Coinhive would later improve this functionality by implementing a scaling feature to only mine a certain percent of the CPU.

Cybercriminals using vulnerable websites to host malware wasn’t new in 2017, but injecting sites with JavaScript to mine Monero definitely was. Coinhive maintains there is no need block their scripts because of “mandatory” opt-ins. Unfortunately, criminals found methods to suppress or circumvent the opt-in, as compromised sites we’ve evaluated rarely prompt any terms. Since Coinhive received a 30 percent cut of all mining profits, they likely weren’t too concerned with how their scripts were used (or abused).

CryptoJacking exploded onto the scene to actually overtake ransomware in late 2017 and early 2018. After all, ransomware requires criminals to execute a successful phishing, exploit, or RDP campaign to deliver their payload, defeat any installed security, successfully encrypt files, and send the encryption keys to a secure command and control server—without making any mistakes. Then the criminals still have to help them purchase and transfer the Bitcoin before finally decrypting their files. It’s a labor-intensive process that leaves tracks that must be covered up.

For criminals, cryptojacking is significantly easier to execute than ransomware. They can simply inject a few lines of code into a domain they don’t own, then waits for victims to visit that webpage. All cryptocurrency mined goes directly into the criminal’s wallet and, thanks to Monero, is already clean. Then its easy enough to trade that hard-earned Monero for Bitcoin on an exchange—and no one is ever the wiser.

Learn more about the cryptocurrency market in part 3 of this post.